by Ken Ruddock

THIS YEAR is the 80th anniversary of the General Strike of May 1926, a momentous event in the history of British trade unionism – one with lessons for today’s trade unions and the labour movement in general.

To understand why the General Council of the Trades Union Congress came to call a general strike starting on midnight of 3rd May 1926, with the support of 3,600,000 workers, it is necessary to go back in time to the years of the First World War 1914-1918 and even before.

During the years running up to 1914 there was growing unrest in Europe. The Socialist International agreed that in the event of war, it should be opposed. On the eve of war, mass demonstrations took place up and down the country. Trafalgar Square saw a huge demonstration addressed by labour leaders Keir Hardy and Arthur Henderson in opposition to war.

Before the month was out, the Labour Party decided to support the Tory government’s war, and along with the TUC, decided that “an immediate effort be made to terminate all existing disputes, whether strikes or lock-outs, and wherever new points of difficulty arise during the war a serious attempt should be made by all concerned to reach an amicable settlement before resorting to strikes and lock-outs.”

This left the workers defenceless against the employers’ attacks on wages and conditions, and was soon followed by the “patriotic” Labour leaders signing the “Treasury Agreement” which neutralised the unions for the duration of the war. It brought with it, in some industries, a complete ban on strikes and compulsory arbitration.

However this did not deter the workers entirely and there were a number of unofficial strikes when employers took advantage of the war to break agreements.

During the many struggles in defence of workers’ conditions, a new form of militant unionism grew: that of the shop stewards who, elected as workshop representatives and leaders, became the answer to collaboration with the state machine.

Examples of the strength of this movement are illustrated by the Clyde strike in June 1915, which arose from an anomaly in rates of pay. The Glasgow district committee of the Amalgamated Society of Engineers made an application for an increase of two pence an hour. This was refused with an offer of a halfpenny and the engineering workers in 15 establishments ceased overtime working.

This was opposed by the ASE executive, who, whilst siding with the employers, organised a ballot on the employers’ offer. It was rejected by 8,927 to 829, resulting in an increased offer of one penny and an increase in piece rates was won.

In July 1915 the South Wales miners, part of the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain who had refused to be a party to the “Treasury Agreement”, made demands for a new agreement on wages and conditions from the mine owners, who were taking advantage of the war to improve their own position.

When the employers rejected the demand out of hand, the Miners’ Federation decided by a majority of 42,850 to strike. Despite threats from the Government 200,000 miners stood firm. In less than a week this resulted in the Government over-riding the mine owners and conceding the main demands.

There were other disputes but it was the Clyde strike that had marked the emergence of the shop stewards as the backbone of a new form of workshop organisation. Out of the strike the Clyde Workers’ Committee was formed, with William Gallacher as chairman (Willy Gallacher became a Communist MP after the war).

Workers’ committees sprang up in London, Sheffield and in other centres of industry and in 1916 a national Shop Stewards’ Movement was formed. The shop stewards became the effective defenders of the workers in the face of the inactive union executives.

The Government had introduced a Munitions Act, under which workers virtually lost all rights of protest. In July 1916 over 1,000 workers were convicted under this Act. It was not only in the industrial field that workers were becoming more militant. Rents strikes against rapacious landlords grew.

In 1917 the news of the Russian Revolution added to the revolutionary spirit of the workers.

With the end of the war in 1918, the Labour Party withdrew its Labour Ministers out of the coalition government and won what became known as the Khaki election, because of the returning soldiers taking part.

The change of government did nothing to improve conditions for the workers. It was again left to the workers to fight their own battles with the employers.

On the Clyde the strike was for a shorter working week. The national officials of the unions failed to support it and it ended in a fortnight. Then came the miners, the MFGB demanded a 30 per cent increase, a six-hour day and nationalisation of the mines.

The Government had continued to control the mines after the war and was now facing a strike with exhausted stocks of coal. The miners had formed the “Triple Alliance” with the railway and transport workers, who had also made claims. The Government was faced with a general strike.

The Prime Minister, Lloyd George, offered the miners a Royal Commission on the one hand, and a threat of armed force on the other. The MFGB president, Robert Smillie, caved in to the threat and won a narrow majority for acceptance of the offer.

The commission, presided over by Mr Justice Sankey, subsequently recommended nationalisation. But the Government, despite the promise to implement the commission’s recommendations, refused to comply and provoked a strike in the Yorkshire coalfields during July and August 1919.

The years that followed deserve an article for themselves. The Lancashire cotton workers won a strike for a 48-hour work and a 30 per cent increase in wages when 300,000 of them came out. The railwaymen struck for a week against threatened wage cuts and won improvements against threats from the Government. And it is worth noting that it was only the conservative influence of JH Thomas that prevented the strike widening into a general move forward. Other sections of the labour force, including dockers, made gains.

All these were during the post-war boom, which was coming to an end, bringing with it a rise in unemployment of two million in the slump of 1921. This inevitably brought with it a general attack on workers’ wages and conditions.

The first sections to come under attack from the employers, with the support of the Government, were the coal miners. They had rejected the coal owners’ demands and were locked out. The Miners’ Federation invoked the aid of the Triple Alliance, which called for a strike on 12th April.

Whilst the workers were prepared to take action, the leaders of the Triple Alliance were not enthusiastic and postponed the strike to 15th April. During this delay Frank Hodges, secretary of the Miners’ Federation, took it upon himself to offer a temporary settlement at a meeting of MPs. The following day his unauthorised action was disowned by his executive.

But the damage had been done and the alliance leaders withdrew their support. This day became known as “Black Friday”. The result was catastrophic. Workers felt they had been betrayed. Three of the four leading personalities associated with Black Friday deserted to the other side. Frank Hodges became a director of the Bank of England; JH Thomas left public life, Robert Williams became a spokesman for the National Government. The fourth member was Ernest Bevin.

During the next three years the effect of Black Friday was to undermine the morale of the workers who were left to fight defensive actions. The miners were defeated and six million workers suffered wage cuts. The employers used lockouts to break any resistance. The effect on trade union membership was dramatic.

But by the end of 1923 there were signs of recovery and workers started to regain their fighting spirit with strikes – many unofficial – of builders, agricultural workers, boilermakers, dockers and seamen.

January 1924 saw the election of the first Labour government under the leadership of Ramsay MacDonald. During an official strike of railwaymen that was taking place at the time, MacDonald showed no sympathy with Aslef, the union leading the strike. This action eventually won some concessions in spite of disunity from the National Union of Railwaymen, which instructed its members to continue working.

The year continued with more unofficial disputes in the shipyards and railway shops. In London the tramway workers struck for higher wages; the busmen joined them and the Tube men were considering sympathetic action. McDonald declared he would invoke the Government’s Emergency Powers Act, which empowered him to declare a state of emergency. Only the simultaneous ending of the strike prevented military intervention.

For some time militant workers had been moving to the left. They had created the National Minority Movement at a conference in London in August that year, with the veteran Tom Mann as president and Harry Pollitt – who had gained a reputation representing the boilermakers as a delegate to Labour Party conferences – as secretary.

By this time Harry Pollitt had become secretary of the Communist Party. The movement had grown in the South Wales and Fife coalfields and had secured the election of AJ Cook as secretary of the MFGB, replacing Hodges after his forced resignation.

In September a new spirit could be seen in the trade unions. Whilst the Labour government had been defeated in the October election, the September TUC congress adopted an Industrial Workers’ Charter; gave the General Council new powers to intervene in disputes, and to draft a scheme for linking the unions into a united front for improving workers living standards. The council was also instructed to call a special congress to decide on industrial action if there was a danger of war.

By 1925 the British capitalists were facing a desperate economic struggle to regain their world position. Prime Minister Baldwin had declared that “all workers in this country have got to take reductions in wages to help this country get on its feet”.

The Miners’ Federation, always the first to come under attack, refused the mine-owners’ demands and received the “complete support” of the TUC General Council, which appointed a special committee to cooperate with the miners in resisting this attack.

The committee, with the support of the railway and transport workers, drew up plans for an embargo on all coal transport in the event of a miners’ lockout. A special conference of union executives endorsed the plan on the day before the mine-owners’ deadline: 30th July.

The Government, unprepared for such action, retreated and announced a nine-month subsidy to enable a Royal Commission to conduct an inquiry. The mine-owners withdrew their proposed lockout. That day is now known as Red Friday.

The General Council declared that the defeat of the Government was “an immense stimulus to every trade unionist”. But communists warned that “the capitalist class will prepare for a crushing attack on the workers” and continually called for preparations to repel such an attack.

The capitalist state had, following its setback on Red Friday, started preparations for a counter attack by forming an “unofficial” Organisation for the Maintenance of Supplies” with a Central Council made up of high-ranking admirals, generals and retired officials of the state, for the purpose of organising strike-breaking “black legs”, special constables and fascist elements.

This organisation, known as OMS, became an official arm of the state, supporting the capitalist employers. Winston Churchill, at the time Chancellor of the Exchequer, made it clear that their action on Red Friday had only been intended to give the Government time to prepare its counter attack.

There was little reaction to all of this from the TUC’s General Council. But the September congress in Scarborough showed the fighting mood of the workers with a vote of 3,082,000 to 79,000 in favour of revolutionary opposition to British imperialism. The conference declared that the aim of the unions, in conjunction with the Labour Party was for the workers’ overthrow of capitalism and pledged itself to strengthen workshop organisation.

Despite these brave words, the congress saw the election of two men associated with Black Friday – JH Thomas and Ernest Bevin. They were joined by WM Citrine as General Council secretary following the death of Fred Bramley. This moved the balance of force on the General Council to the right.

At the following Labour Party conference Thomas and Bevin associated with MacDonald in a counter demonstration to the Scarborough congress. Pressure was put on the unions not to elect communists to the Labour Party.

The Government saw the green light and within a fortnight had jailed 12 Communist Party leaders after the biggest state trial since the Chartist days.

The Miners’ Federation, concerned at the turn of events, made efforts to form an industrial alliance of key unions to prepare for the conflict, which were wrecked by the withdrawal of Thomas’s NUR.

The Royal Commission on the coal industry headed by Sir Arthur Samuel, later to become a lord, produced a report in March 1926, which was vague in its view on recognition of the coal industry under state control. But it was strong in its view that miners should accept longer hours and lower wages.

The miners’ delegate conference on 10th April disillusioned the General Council by standing firm and so did the Minority Movement conference held in late March, attended by 883 delegates representing a million trade unionists, supporting their fight.

The mine owners immediately declared they would only negotiate on a district basis, and gave notice of a lockout for 20th April. They demanded wage reductions so severe that even their president, Evan Williams, admitted the resulting wages would be “miserable”.

In response the TUC General Council regained its backbone in support of the miners and on 27th April decided at last to draft plans for large scale action if necessary.

Negotiations continued the following night of 29th April and the following day. But it became clear that the Government, having completed its preparation, was determined to provoke a conflict. The General Council’s negotiators, of which Thomas was a leading member, reported to union executives the following morning and a vote was taken endorsing a General Strike order by unions representing over 3,600,000 members to fewer than 5,000.

They announced that specified unions would strike as from midnight Monday 3rd May.

They planned that specified trades would be called out in two sections. The first included all transport, printing, iron and steel foundries, heavy chemicals and building workers (except those working on housing and hospitals). The maintenance of food and health services was to be covered by the unions concerned.

Whilst these preparations were going ahead, the General Council still maintained that they had a right to negotiate for the miners, even if it meant a reduction in wages.

But when the Natsopa members refused to print an anti-union leading article in the Daily Mail and went on strike, Baldwin demanded that if negotiations were to continue, the General Council should withdraw the notice of a General Strike. This he made impossible, and despite the misgivings of the General Council, the dye was cast and at midnight on Monday 3rd May an army of a million workers struck.

The next day the TUC communiqué said: “We have from all over the country reports that have surpassed our expectations. Not only the railwaymen and transport men, but all other trades came out in a manner we did not expect immediately. The difficulty of the General Council has been to keep the men in what we might call the second line of defence rather than call them out.”

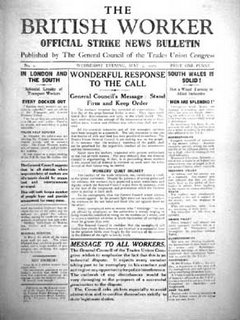

There were no passenger trains, no newspapers. The Communist Party issued a typewritten Workers’ Bulletin. The General Council, always on the defensive, only produced its own news-sheet, the British Worker, after the Government had produced an official British Gazette.

The trades councils and councils of action speedily organised in many parts of the country, so effective that in some major towns nothing moved without a permit from the trades council. The International Federation of Trade Unions declared its moral and financial support if needed.

The second day of the strike, the London taxi-drivers stopped work. The National Union of Journalists (Glasgow) refused to Blackleg. The National Unemployed Workers’ Committee Movement – already suffering from the employers’ attacks – offered assistance to the trades councils and strike committees.

The Independent Labour Party called on its branches to support the strike. The Communist Party issued a statement in the British Worker with the slogans:

1) All together behind the miners;2) Nationalisation of the mines3) Resignation of Baldwin; formation of a Labour government.

By this time the police were more aggressive with baton charges against strikers in crowds in the streets and making summary arrests. Communist MP Saklatvala was sentenced to two months imprisonment for a speech on May Day.

Days four and five of the strike saw all electrical stations in London on strike, with the withdrawal of electricity from the House of Commons. The Government issued an indemnity to troops for any action considered necessary to maintain order.

There were more battles with police in many towns such as Liverpool and Hull. In London there were 36 arrests. Local strike committees made arrangements with the Cooperative organisation for the supply of food. Communist Isabel Brown was sentenced to three months imprisonment.

On day six, Purcell, the leader of the General Council’s strike organising committee, declared that the Government had issued warrants for the arrest of himself and Ernest Bevin, who was then secretary of the Transport Workers’ Union and a member of the General Council. Other sources reported that the Government had decided to arrest members of the General Council and local strike committees, to call up the army reserve and to repeal the Trades Disputes Act.

At a high mass, Cardinal Bourne declared the General Strike to be a sin against God.

JH Thomas said: “I have never disguised that I did not like the principle of a General Strike.”

On day seven the General Council negotiated with the Cooperative Wholesale Society for credits to the trade unions. It also called for a five per cent levy on all workers not yet on strike.

Day eight saw the General Council issue the strike order for all engineering and shipbuilding workers not yet affected by the strike. Despite increased arrests – 100 in Glasgow and another 25 in Hull – the BBC announced: “There is as yet little sign of a general collapse of the strike.”

And yet on the same day the General Council accepted a rehashed Royal Commission report by Sir Herbert Samuel and called off the strike without any guarantees of any kind, and in the face of miners’ opposition. The General Council of the TUC presented itself at Downing Street at 12 noon on 12th May and informed Baldwin that “the General Strike is being terminated today”.

The General Council had not only treacherously abandoned the miners but had left the trade unions individually to negotiate their members’ return to work, with only a vague understanding from Prime Minister Baldwin that they would return to work on the same conditions as at the start of the General Strike.

The result was a Government official communiqué saying that they would not compel employers to take back workers who had taken part in the in the strike and that the Government had not taken on itself any such obligation.

The individual unions instructed their members to stay out until agreement with employers was reached, which took another four days. The miners refused to accept defeat and fought on until December.

Despite its defeat, the General Strike was the greatest act of defiance against the British capitalist class. It showed a unity of the working class never seen before and which could be built again, provided the lessons of the fallibility of social democratic leadership are understood.