by Caroline Colebrook

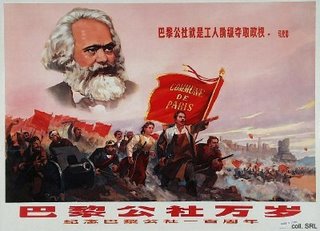

NEXT month marks the 135th anniversary of the Paris Commune, when the working class of Paris seized power in their own city and established the world’s first workers’ government. It did not last long and it was drowned in blood by armed forces of the French government.

But it sent a message of liberation and hope to workers throughout the world and a message of fear to capitalists and landowners. Many lessons were learnt from its mistakes and from its successes. Without it, the great socialist revolutions of the 20th century would not have been possible.

THE PARIS of the 1860s and 1870 had been rebuilt by architect Baron Haussmann at the request of Napoleon III, with wide, well-planned boulevards and fine houses.

It was a time of industrialisation and a growing middle class (the original use of the term “bourgeoisie”) with plenty of wealth. But the resulting inflation in prices and rents left Parisian workers desperately hard up – and angry about it.

Paris has a strong revolutionary tradition from the revolutions of 1789, 1830 and 1848. The strong feelings against royalty, wealth and privilege remained – as did the proclaimed revolutionary virtues of Liberté, Egalité, and Fraternité (Liberty, Equality and Brotherhood).

The Parisian workers were also angry when the Emperor Louis Napoleon engaged in an unnecessary war with the Prussians. The French army was undermanned, under-equipped and badly led. On Friday 2nd September it was defeated at the battle of Sedan on the Belgian border. The Emperor was taken prisoner and immediately abdicated.

When the news arrived in Paris a crowd gathered outside the Hôtel de Ville (City Hall). There was a power vacuum and a new republic was declared by Léon Gambetta. A temporary government of National Defence was declared, which included the sitting National Assembly deputies for Paris – since, with the Prussians marching on Paris, there was no time for new elections. This government had no pre-agreed political programme. The Empress Eugénie fled to England.

There were further defeats for the French army as the people of Paris prepared to repel the Prussians, including repairing the old city walls. The National Guard, founded in 1789, still existed and was rapidly expanded by volunteers to 350,000-strong – bigger than the regular French army defending Paris at the time. But it was a very mixed bunch of people from many different backgrounds.

Many workers who had been thrown out of their jobs by the war joined for the pay of 1.50 francs-a-day plus 75 centimes for a wife. Women also joined the National Guard as – cantinières – officially carrying food and drink to the fighters but actually doing a lot of fighting as well. When a guardsman fighting the Prussians fell, often a cantinière would take up his rifle and carry on the fight.

Paris prepared for a siege by bringing in huge quantities of food, including livestock. Commentators at the time remarked at the public parks full of sheep. But even while the people of Paris were preparing to put up a bitter struggle, the temporary government was seeking a peace deal with the Prussians.

Once the siege took hold, there was a news blackout inside Paris. People tried communicating with the outside using carrier pigeons carrying microfilm – a new development then – but only 59 out of 392 got through.

Manned balloons were a little more successful. They presented a huge target but only five out of 65 were shot down. But they were not easy to control and easily blown off course. They landed as far away as Holland, Bavaria and even Norway.

Outside of Paris the war with the Prussians was still going badly for the French, with another major defeat at Metz.

In spite of the all food that had been stored in preparation for the siege it soon brought great hardship. There was no rationing at first so the poor suffered disproportionately as food prices rocketed.

Strange things started to appear on menus, including animals from the zoo. During the siege records show that 65,000 horses, 5,000 cats, 1,200 dogs and an uncounted number of rats were eaten. By January 1871 they introduced bread rationing.

Fuel was also in short supply so people cut down trees and burnt them and their furniture.

Throughout the siege the Prussian bombarded the city with their huge guns, killing 97 but hunger and illness killed many more. In December 1870 the total death toll was 11,865 and in January 1871 it was 19,233.

The people were angry with the temporary French government for not striking back at the Prussians. There were no plans for a strike by the National Guard.

On 18th January the Prussian declared their empire at Versailles. In Paris there was talk of throwing out the government and setting up a commune. On 28th January the French government negotiated an armistice with the Prussians.

Paris felt utterly betrayed. The terms of the armistice allowed the Prussians to enter Paris for two days to celebrate their victory. The people of Paris turned their backs, shut their doors and dressed in mourning. After the Prussians departed they cleaned the streets.

The new National Assembly was pro-royalist and opposed to the republicanism of Paris.

Adolphe Thiers was elected head of the new government and he drew up a peace treaty with Prussians.

He then stopped pay for the National Guard and ordered Parisians to pay back commercial debts and rent arrears they had run up during the siege.

Anger was rising in Paris and on Saturday 18th March Thiers sent General Lecomte with orders for the army to take over the National Guards’ cannon position in Montmartre, overlooking the city. The National Guardsmen were overpowered and locked up.

But the army had forgotten to bring horses to transport the guns out of Paris so they had to wait until the next morning. Very early the next morning a young socialist, Louise Michel, came to deliver a message to the National Guard. She noticed the army had taken over the gun emplacement and raised the alarm throughout Paris.

Later she wrote: “I went down, my rifle under my coat, crying ‘Treason’. A column was forming… Montmartre was waking. The call to arms was sounding out. I was returning indeed, but with the others, to the attack on the heights of Montmartre: we ran up at the double, knowing that at the top there was an army in battle formation. We expected to die for liberty. It was as if we were lifted from the earth.”

Crowds gathered around the soldiers. The people of Paris had paid for those cannons to fight Prussians. They were not going to let the army use them against the city. The people appealed to the soldiers. An officer ordered them to fire on the crowd but the soldiers refused. They turned their rifles upside down.

General Lecompte was arrested, along with General Clément Thomas, an ex-commander of the National Guard.

The cannons fired three blank shots to tell the people of Paris that the guns were still theirs. They began to build barricades. Regular troops retreated to their barracks and the Red Flag replaced the Tricoleur on the Bastille Column.

Confusion reigned – nothing had been planned and no one was in charge.

A crowd stormed the house where the two captive generals were being held and shot them. Thiers realised he had lost control of Paris. He went to the Hôtel de Ville and ordered the government to withdraw to Versailles. They were swift to comply, jumping out of windows, dashing through underground tunnels and clambering into their carriages in their haste to get away. By evening the Red Flag was flying over the Hôtel de Ville.

After they left a new mood of freedom s wept across Paris. Although still no one was formally in charge, streets were swept, cafés stayed open. There was no looting and less crime than normal. The National Guard was paid regularly and public relief was handed out to the poor. Many wealthy people fled, saying they did not like “the control of workmen”. As in previous revolutions, people addressed each other as “citizen”.

Outside Paris, the government waited in Versailles for chaos and collapse.

On 26th March elections were held and two days later the Commune was proclaimed. Red sashes and red flags abounded throughout the city.

A member of the Commune, Jules Vallés, wrote in his newspaper Le Cri du Peuple: “Today is the festive wedding day of the Idea and the Revolution. Soldier-citizens, the Commune we have acclaimed and married today must tomorrow bear fruit; we must take our place once more, still proud and now free, in the workshop and at the counter. After the poetry of triumph, the prose of work.”

Thirty out of the 90 Commune members were working class – a high proportion for that time. There were no formal political parties in the Commune – they were all socialists but aligned in loose groupings: Jacobins, Blanquists and communists. They were all communards.

The Commune gave working people enormous confidence to do things they had never done before or been allowed to do Many other French cities followed suit and set up their own communes, including: Lyons, Marseilles, Toulouse, Narbonne, St Etienne, Le Creusot and Limoges. But they were all quickly crushed by the Versailles government.

Thiers imposed news barrier so that once again people inside Paris were cut off from news from the outside and vice versa. The outside world was told only Thiers’ version of events. He portrayed the Communards as monsters.

The Communards failed to confront the Thiers government or to seize the banks. If they had, they would have been in a stronger position to resist. They were busy planning social reforms but failed to plan to defend the Commune militarily.

The Commune did have arms and men – which Thiers did not have at first. But the Prussians, alarmed at the prospect of working class revolution, allowed Thiers to recruit and train a new army. He had no doubts that this was a civil war.

The Commune had three military leaders: Lullier, Cluseret and Rossell. They were professional soldiers but they were frustrated by a lack of clear military policy. They were impatient with the new democratic procedures and unable to convey the urgent need to organise the defence of Paris. After seven weeks, they quit.

The Commune did launch one attack against Versailles on 3rd to 4th April. Three National Guard column set off proudly and jauntily but they were outmanoeuvred by the Versailles troops and limped back tired, wounded and dirty. Many were killed and 1,200 taken prisoner while Versailles lost only 25 dead and 125 wounded.

The Versailles government and the wealthy who had fled Paris treated the prisoners shamefully – cursing them, beating them and spitting on them.

After this morale in the Commune fell and divisions began to appear. The Commune was also getting a very bad press internationally. The London Times reported: “The men of the Commune do not intend to be disappointed. They have promised themselves to annihilate Paris, its fortunes, its commerce, its population – and they keep their word.

“Never was the work of destruction carried on with a more wicked and brutal perseverance.”

Communards were called “the mob, red insurgents, bandits, anarchists, convicts, scum, moral gangrene, socialists”.

Inside Paris news was communicated by newssheets posted on to walls and by readings at political clubs – often located in churches. Readings were followed by discussion on all manner of topics – including religion, women’s equality, the abolition of marriage and how to win the civil war.

Women played a very active role in all this. One woman speaker told a club meeting: “Yes, you women are oppressed. But just have a little more patience, for the day that will bring justice and satisfaction for our demands is rapidly approaching.

“Tomorrow you will belong to yourselves and not to exploiters. The factories in which you are crowded together will belong to you; the tools placed in your hands will belong to you; the profit that results from your labour, your care, the loss of your health, will be shared among you.”

There were around 90 trade unions active in the city. Workers’ cooperatives were set up – supported by the Commune. The Commune allowed workers employed in factories and workshops that had been abandoned as the owners fled the city to take them over as cooperatives.

Church control of education was abolished. People were given three years to pay off debts run up during the siege. All public officials were elected; there was a cap of 6,000 francs on top salaries and the Commune paid out to redeem all household goods like bedding and clothing that had been pawned. There was free clothing, food and school materials for children.

The famous artist Courbet was a Commune member. He wrote: “I’m enchanted. Paris is a veritable paradise; no police, no outrages, no quarrels, no exactions of any kind. Paris is moving under its own steam as smoothly as you could wish. We must try and always be like this.”

But in the background, the guns of Versailles continued to bombard Paris. The Prussian army, nearly forgotten, was still there. The Prussians supported the Versailles government against the Commune. They were terrified it would inspire socialism in Germany. On 21st May the Versailles army attacked.

The people of Paris put up barricades to defend themselves but though these delayed the advance of the government troops, they did not halt them.

There followed what was called The Week of Blood as the people of Paris fought a bitter but losing battle to defend the freedom of their city.

The troops entered on 21st May Versailles by the Saint-Cloud gate. When news reached the Communards in the Hôtel de Ville the final Commune session ended as members left for the barricades. No one was left behind to direct the fight except Delescluze, the civilian delegate for war.

He sent the following message to the barricades: “Enough of militarism, no more staff officers with gold embroidered uniforms! Make way for the people, the bare-armed fighters! The hour of revolutionary war has struck. The people know nothing of elaborate manoeuvres, but when they have a rifle in their hands and cobblestones under their feet, they have no fear of the strategists of monarchist school.”

It did no good. It left the people of Paris to fight, every man and women for themselves, with no strategic planning or coordination. There were many heroic stands at the barricades, including the Women’s Battalion defence of Place Blanche but the government troops took the city, with utmost brutality.

They shot men, women and children out of hand wherever they took them. Thiers had promised no retaliation but 20,000 Parisians were killed in one week.

The London Times, which had opposed the commune, protested about “the inhuman laws of revenge under which the Versailles troops have been shooting, bayoneting, ripping up prisoners, women and children during the last six days.”

Retreating Communards torched many large public buildings and after this a scare story was put about that women Communards – dubbed Pétroleuses – were starting fires everywhere. This led to many women being shot on sight on suspicion of being incendiaries.

Two hundred Communards made a last stand against a wall in the top corner of Pere Lachaise cemetery. The next day 147 prisoners were taken to the same spot and shot.

The killing continued after the Communards had all been killed or taken prisoner; 34,722 prisoners were put on trial and many executed. It is estimated that between 20,000 and 25,000 were killed one way or another.

The new government erected a new church, Sacré Coeur, on the heights of Montmartre as a religious gesture of atonement for the audacity and sacrilege of the Commune. Now a famous Paris landmark, this church remains unpopular with left-wing Parisians. Theirs was made President of the 3rd Republic in August 1871.

The Paris Commune failed but its lessons echo through history. After it fell Marx and Engels wrote of the necessity for a dictatorship of the proletariat to be established immediately after any socialist revolution to consolidate it and defend it against counter revolution.

Without the lessons of the Commune, the socialist advances of the following century would have been impossible.